Virtual Production (VP) enables real-time visualization of digital scenarios in filmmaking, significantly enhancing remote collaboration and reducing costs, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. The VPSN research project addresses the need for VP-trained personnel by offering workshops and resources to prepare educators and students, emphasizing VP’s potential to revolutionize both creative industries and educational curricula.

In this article, we share one of our recent research reports, which we had sent and published with the CONFIA24 Conference Proceedings. The proceedings will be part of the CONFIA Publications 2024, and will be available here: https://confia.ipca.pt/publications

CONFIA is an international conference on illustration and animation, organized by IPCA’s School of Design within the Master’s Degree in Illustration and Animation. A space for debate and exploration on design and image, the conference seeks for original submissions, encouraging the participation of artists, cultural industries and the academic community.

The research is written by José Raimundo affiliated with the Polytechnic Institute of Cávado and Ave in Portugal, partners of VPSN.

Abstract

Virtual Production (VP) represents a transformative shift in filmmaking, enabling real-time visualisation of digital scenarios and visual effects during production, a departure from traditional post-production methods. Amidst the COVID-19 pandemic, VP gained relevance by offering cost-effective solutions and making off-site and remote collaboration among cinema crews and film industries possible. However, the adoption of VP technology and procedures is hindered by the lack of trained personnel within higher education institutions. The Virtual Production Studios Network (VPSN) research project intends to fill this gap by preparing teachers and students to engage with VP and advance VP studios. To do so, VPSN provides educators and professionals access to blended-learning and hands-on workshops, to familiarise them with VP so they become the future of the creative industries. This article reports the experience gained from VPSN-hosted activities, participants showed adaptability and resilience, and the willingness to do real-time improvisation, something key for attaining VP success. Despite the challenges, such as the steep learning curve to harness the VP knowledge ecosystem, we highlight the importance of building understanding among film crew members to attain effective collaboration. The integration of VP into education curriculums holds promise in enhancing the preparation and learning of students. We were able to identify three main contributions: 1) VP learning materials have great potential for revolutionising diverse fields beyond the audiovisual; 2) VP processes can stimulate the search for new creative results and aesthetic trends, and, the improvisation of ways to work with available equipment at the margins of VP; 3) VP processes roots on the power of simulation, something with great potential to influence and enhance work disconnected from audiovisual media. In sum, VPSN’s initiatives underscore the transformative potential of VP in education and industry, offering a pathway for students and professionals to navigate the digital production landscape.

Keywords: Virtual Production; Animation, Education; Game Engines; Mocap

Introduction

Virtual Production (VP) is a groundbreaking technological approach to take traditional filmmaking processes into digital realms, by creating animated, realistic real-time digital scenarios or VFX, and displaying them, e.g., in high-density led panels volumes. Unlike traditional methods where VFX visualisation occurs during editing, VP allows this to occur during production [1,2]. This significance can be traced back to amidst the COVID-19 pandemic remote hiring necessities, enabled by technological advances. VP makes film, animation, game, and art creation more cost-effective, allows real-time processing and display of film sets using accessible game engines, and, off-site distanced distributed collaboration, something that transformed work on this area’s related industries [3]. VP is underlined by benefits but also shortcomings, like the lack of trained personnel by higher Education Institutions (HEIs) apt to work on this fast-paced, advancing technology landscape [4].

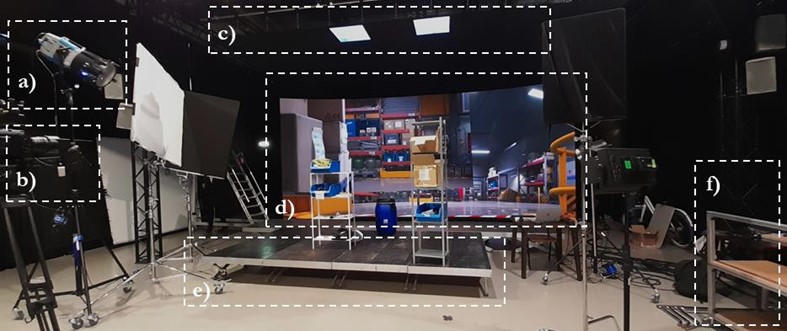

The Virtual Production Studios Network (VPSN) intends to respond to this shortcoming by preparing students to engage with VP upon graduation, and by setting strategies for advancing VP studios. VPSN is a research project consortium of HEIs led by VIA University College in Denmark, Breda University of Applied Sciences (BUAS) in the Netherlands, the NORD University in Norway, and the Polytechnic Institute of Cávado and Ave in Portugal. To address the mentioned shortcoming VPSN aims to provide the following knowledge resources: 1) for teachers and professional trainers in educational and creative industries, the access to market and academic research, hands-on practices and VP teaching and training curriculums for integration in HEIs education curriculums; 2) for students and graduates from creative industries in Europe, the theoretical and practical information on how to use VP studios; 3) for the creative industries (animation, gaming, film, or digital media), indirect innovative benefits hinged on student practices with skills and know-how in VP [5]. We consider that VP practices are valuable to produce animations for virtual or augmented reality applications, because we carried the development of animations as digital, real-time controlled, movie mock-up backgrounds to be registered to a physical, Extended Reality (XR), film studio, depicted in Figure 1.

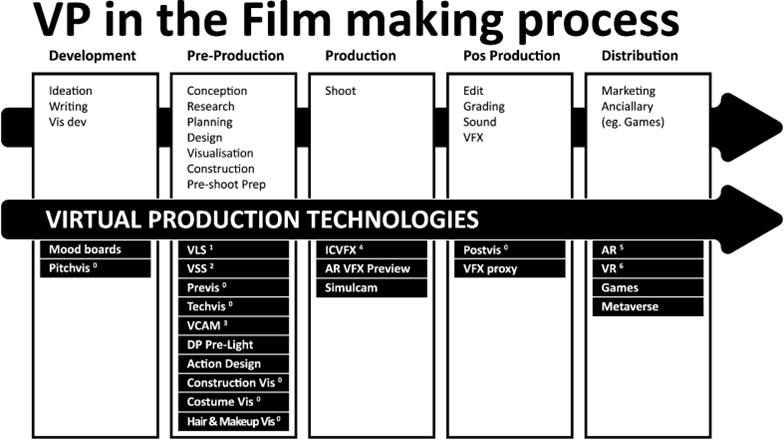

The BUAS XR stage contains technology and traditional resources to do small VP, XR is a common umbrella abbreviation that encompasses a variety of terms, like Augmented Reality (AR) and Virtual Reality (VR). As with similar stages, it uses a led volume as an enhanced chroma-key screen, i.e., an augmented, real-time virtual scenario, and several flavours of MOCAP to sync actors, cameras, lighting, and virtual 3d asset movement [6]. With this in mind, this article reports the results of two VPSN training, hands-on workshops, the first, involving teachers and professionals, the second, involving students. By reporting these empirical experiences, we intend to clarify benefits and shortcomings of VP processes and technology for education, animation, cinema, and related industries. The VPSN education pipeline involves several stages akin to traditional filmmaking but follows specificities which are depicted in Figure 2.

Both traditional and VP follow the same key development stages, but for the latter the emphasis is on pre-production, an already big parcel in any movie production. VP adds the work on virtual asset components and their operation which characterise SFX done in productions such as The batman (Warner Brothers, 2022) or The Mandalorian (Disney +, 2019). We won’t delve deeper in VP jargon as it is already documented [8], and because it would be beyond the scope of an article focused on providing a glimpse of VP benefits and shortcoming for educators and professionals interested in setting a foot in the area.

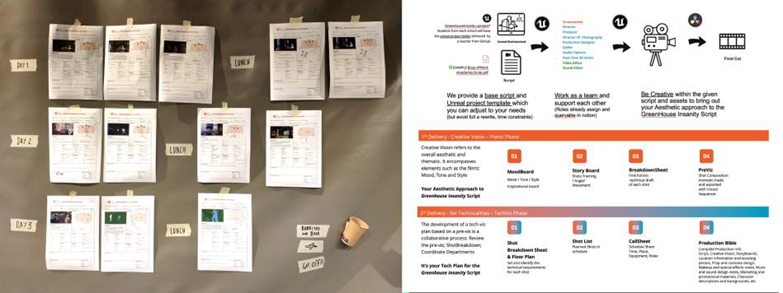

Initial development for the teacher’s workshop was anchored on a script that situates film action on a fictitious abandoned greenhouse overtaken by two scientists to carry out plant growth experiments. Manuals and content were prepared by BUAS beforehand to sustain participant blended learning, between off-line self-allocated hours, and on-line presential workshops. Blended learning was used as acquiring VP knowledge in its many sub-areas requires a lot of time investment. Under the VPSN time-framing, teachers would receive training first and act as film crew members in a small VP production, a process that would then be replicated by students in another workshop under these same teachers’ supervision. Pre-workshop activities involved traditional movie pre-production with some emphasis on the specificities of VP. This process began with initial offline training using Epic’s video tutorials about Unreal and Davinci Resolve software. The predefined script enabled prompt traditional pre-production work from the teacher’s crew until April 21st 2023. Pre-production involved the elaboration of creative visions, storyboards, breakdown-sheets and tech-plans, some of which are illustrated in Figure 3.

Learning software and elaborating the pre-production documentation enabled developing movie previsualizations (Previz), a 3D simulated environment that allows rendering an animated sequence, to check if it meets final film expectations and shooting doability, and to pinpoint unpredicted aspects to explore. Each partner institution crew had to develop their own previz and documentation from the script to maximise training, and only one solution would be produced depending on feasibility and potential possibilities to push experimentation in the BUAS XR stage, e.g., day-to-night lighting accelerated timelapses with multiple actor instancing, as depicted in figure 4.

The previz virtual scenario was also used to check if it would comply with the minimum viable technological performance requirements to be displayed in BUAS XR led volume in real time, and again if it would be close to the wanted result [8,9], a screenshot of a previz made by IPCA, developed in UNREAL is depicted in Figure 5.

Experiential on-site workshops ensued next, as teachers and VP professionals from the VPSN HEIs consortium travelled to the University of Applied Sciences in Breda in May 2023 in its XR Stage facility, to develop a VP short from the pinpointed pre-production work version. Students developed their own VP in January 2024, the only difference was that they were mentored during blended-learning activities by the same teachers that took the trainers workshop, and used a self-proposed script, results are depicted in Figure 6.

Discussion

Both workshops operated similarly in terms of process and outcomes for both teachers and students, regardless of being different target groups. The time to learn and to familiarise oneself with VP software was (and still is) of utmost importance, something that sits at the front door for anyone trying to enter this new world and trend in filmmaking. Anyone committed can, with modest computing hardware, make this preparation independently of having access to a VP equipped studio. Still, VP is not possible without an extended life-long preparation open to the accelerated changes and updates in the field. This need for commitment was clear for participants in both workshops as those who had previous software or cinematography role experience were quickly assigned to the main film production tasks, such as real-time 3D artist, or director of photography. Those with less experience had the opportunity to level knowledge in other roles such as set production designer or gaffer.

Harmonising the understanding between crew roles proved somewhat difficult because of the natural push and pull between the interests of those focused on cinema and those focused on games. Such challenges may be overcome by developing a common vocabulary through constant content exchange between creatives in both fields [10]. Although a new vocabulary did not emerge, constant dialogue did occur to respond to the workshops’ project-driven nature aspects such as deadlines, and unexpected obstacles emerging during shooting, factors that prevented disagreements. These obstacles ranged from tuning camera MOCAP and the virtual scene to update at a reasonable framerate, overcoming led screen aliasing, dressing the set with zero budget, amongst others.

The obstacles themselves advanced improvisation as a crucial component for VP success, as they indirectly enticed crew members to turn into a well-oiled filming machine, apt to overcome both traditional cinematography and new VP obstacles, like delighting unwanted light from the led volume. Improvisation occurs when crew members respond promptly to other’s improvisation on a given situation, e.g. camera operators follow actors’ improvisation by operating cameras and changing lenses appropriately, gaffers adjust their lighting, and sound recordists adjust their position and settings accordingly [11]. The importance for improvisation extends to many Art endeavours and life circumstances, as dialogue in the film set led to acts of spontaneous creation where crewmembers exchanged information in coordination, i.e. it was not about compromising according to individual perspectives but about creating something new and mutually enriching [12], such spontaneous creation are depicted in Figure 7.

Improvisation occurred during the teachers’ workshop, as we were pressed to shoot scenes under deadlines, e.g., moving the entire set instead of the lighting (camera track remained unchanged), as this proved easier due to the limited led volume space. This solution allowed economy of means, time, and made consistent lighting, one of the most difficult aspects to control in VP, possible. In the students’ workshop, improvisation occurred e.g., through the repurpose of stage platforms as balconies to physically crop the led volume, and using light supports to create an interior curtain set dressing.

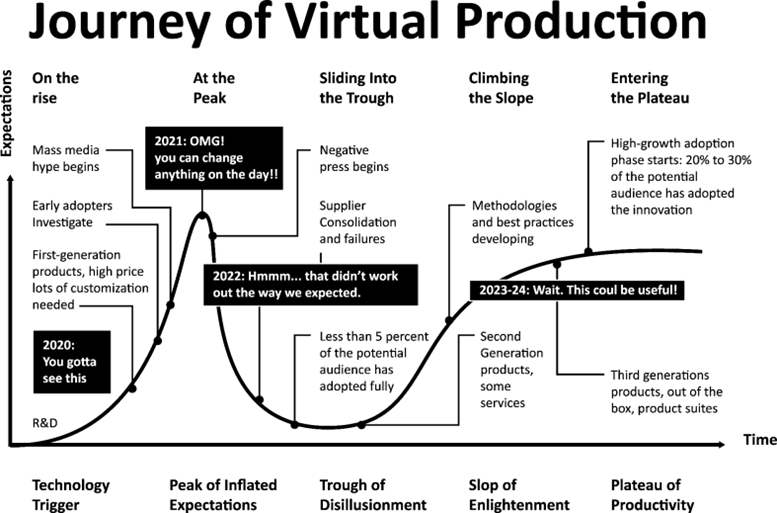

The myriad of obstacles like learning time, communicating among areas of knowledge, or the improvisation solutions on-the-fly, points to commonalities between traditional filmmaking and VP, so why insist on using it in the first place? Arguably VP can, with enough training equipment and software, help create SFX or simulated scenarios that would be difficult to attain with traditional means, or prohibitively expensive. However, VP is also far from being a one-size-fits-all solution, as a modest video camera and an outdoor setting coupled with enough creativity can make shooting more accessible and quicker to harness than a fully equipped, optimised XR stage. This concern can be explained by the intersection of Gartner’s hype cycle with VP, which allows to trace the journey of VP technology popularity, as schematized in Figure 8.

Gartner’s hype cycle maps the evolution journey of technological innovations, through peak, disillusionment, and resurgent stages. It is used to make investment educated guesses on novel products. The model is criticised on the fitness and meshing of its components [13], however, we use it here to emphasise the notion that VP must be employed carefully, as it won’t cover all cinematography needs. VP’s current state lies between the Slope of Enlightenment and the Plateau of Productivity, something we believe is due to two main reasons: more mature, scalable, and affordable technology; new intuitive methods and practices, and something new: VP’s adoption by other niches and audiences, like musicians or animators became apparent in a VPSN masterclass depicted in Figure 9.

The masterclass covered advanced Unreal Engine animation, character rigging, MOCAP using Rokoko suits and software, AI content generation and syncing all this with physics simulations and other audiovisual components to create cinematics and broadcasting it through Aximmetry. Equally important was the opportunity to check this instructor’s and other specialist’s portfolios, which asserted the value of work done in other VP niches. The displayed work pointed out that a lot can be made without harnessing every single piece of VP software or hardware, as what really matters is carefully choosing what to use and how to use it to achieve distinguishing results.

Among the workshop shortcomings we can find the effort and minimal necessary time to master the Unreal Engine, as keeping oneself up to date with these skills can quickly become a life-long endeavour. We believe that there is a need for significantly more time to familiarise oneself with core VP software than what was allocated in the off-line portion of the workshops. Further, given that both workshops targeted small film shorts, reaching this goal surpassed learning opportunities for crew members beyond the roles they were allocated in the first place. We are not dismissing specialisation, however, knowing the VP ecosystem as a whole and being able to assume as many roles as possible within it, will make us better professionals. Further, students need to reinforce their communicating skills to better work with each other in the framing of individual film roles, a gap that we witnessed in the offline portion of the workshop which then translated into its face-to- face session. The masterclass, in turn, emphasised the need for more time to learn VP subjects, as we ran into obstacles caused by insufficient learner preparation beforehand and limited time to harness heavily-packed subjects.

By gathering all this information, next we can weave some considerations on how we, teachers, can use lessons learned from the VPSN project activities according to realistic class needs and professional settings in the VP market and industry in our country.

Conclusions

We lecture design and audiovisual related disciplines such as video, and 2D and 3D animation, while targeting the production of a vast array of traditional and digital media content, from editorial printing to cinematography and video games. Therefore, it is of our interest to map VP processes, depicted in Figure 10, to enhance existing curriculums.

Specifically we consider our exposure to LED volumes and camera MOCAP, assisted by Vicon’s Shogun software (which we don’t have access in our institution), Unreal game engine, and post-production and compositing using Da Vinci Resolve (all with steep learning curves and computing requirements that surpass the capabilities of many of our student’s laptops). Because the VPSN workshops process are divided in steps as depicted previously, from pre-production to production, and depend on different tasks and areas of interest, from cinematography to game engines, from MOCAP to set Design and their respective methodologies, we were able to discern three generic contributions:

- Enhancing and systematising learning materials for specific cinematography and audiovisual work processes that can be extended to learning practices in other Design disciplines in the shape of new manuals, briefs and exercises;

- Advancing and stimulating the adoption of improved multidisciplinary cultural practices, range from new aesthetics and techniques, to improvising new ways to work with available equipment at the margins of VP;

- Leveraging the power of software that bridges different production stages while merging physical and virtual worlds enables the creation of realistic simulations which are already a norm across diverse areas of knowledge and industries. As such, even without hardware for leveraging VP, knowing that its process roots on the power of simulation, point this as a means to influence and enhance work disconnected from audiovisual media, e.g., product mockups, architectural and design previz, and other unsought simulation possibilities.

In sum, the VPSN point to the transformative potential of VP in education and industry, as a path for students and professionals to navigate the digital production landscape.

References

- Priadko, Оleksandr & Sirenko, Maksym. Virtual Production: A New Approach to Filmmaking. Bulletin of Kyiv National University of Culture and In: Series in Audiovisual Art and Production. 4. 52-58 (2021)

- Kavakli, M., & Cremona, C. The virtual production studio concept: an emerging game changer in In: IEEE on Conference Virtual Reality and 3D User Interfaces (VR) (pp. 29–37). IEEE Computer Society (2022)

- Advanced Imaging Virtual Production Workflows & Insights, https://youtu.be/81f6FPnWMCI?feature=shared

- Virtual production: From Studio to classroom, https://www.vpstudionetwork.com/

- Batho G. State of VP and its Future Implications, https://vpstudionetwork.com/industry-interview-with-zoltan-batho-g-state-of- vp-and-its-future-implications/About – VPSN. https://www.vpstudionetwork.com/about/

- Rauschnabel, P., Felix, R., Hinsch, C., Shahab, H., Alt, F. What is XR? Towards a Framework for Augmented and Virtual In: Computers in Human Behavior, Volume 133, 2022, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2022.107289.

- Jungherr, , & Schlarb, D. The Extended Reach of Game Engine Companies: How Companies Like Epic Games and Unity Technologies Provide Platforms for Extended Reality Applications and the Metaverse. Social Media + Society. 8 (2022)

- Chanpun, Virtual production: Interactive and real-time technology for filmmakers. Humanities, Arts and Social Sciences Studies 23(1): 9–17 (2023)

- Kadner, THE VIRTUAL PRODUCTION FIELD GUIDE VOLUME 2. Epic Games, https://www.unrealengine.com/en-US/blog/volume-2-of-the-virtual- production-field-guide-now-available

- Dooley, K., & Emery, S. Creating screen stories with game engines: challenges and opportunities for students and researchers working collaboratively across In: Media Practice and Education, 24:1, 21-34 (2023)

- Collins, Aesthetic Possibilities of Cinematic Improvisation. In: Croatian Journal of Philosophy, Vol. XIX, No. 56- McGill University, Montreal, Canada (2019)

- Nachmanovitch, Free Play: Improvisation in Life and Art. New York: Penguin Putnam Inc . (1990)

- Dedehayir, , & Steinert, M. The hype cycle model: A review and future directions Technological Forecasting and Social Change. Elsevier, vol. 108 (C), pages 28-41 (2016)